Broadly, I am interested in twentieth and twenty-first century disruptions to social and cultural practices in East Africa. This includes topics that involve questions of “authenticity” of traditions, the effects of migration on identity, and–to apply Helen Tilly’s framework culturally–how empire served as a ‘living laboratory” for different groups and organizations (and the colonial enterprise at large) to work through beliefs and ideologies of race, gender, and other social constructions such as childhood. I am particularly drawn to questions of how childhood transformed in the seventy years that the British occupied what became Kenya, and what this meant for structures of childhood, the role of children as historical agents, coming of age practices, and how the growth of international aid organizations as impacted children in the Global South. This curiosity led me to recognize that childhood was an incredibly contested space between a multiplicity of groups (and children themselves) throughout Kenya’s colonial era.

My dissertation research examines how childhood was a critical cultural space fought over by the British and various African communities during the colonial period in Kenya. British colonial officials, missionary and nongovernmental organizations, and African communities in Kenya clashed regarding who constituted children, what was acceptable behavior by children, and the perceived responsibility of adults toward children. As conceptions of childhood became globalized through these fraught issues, colonial Kenya became a “living laboratory” for various actors to reconsider and project beliefs regarding children and childhood. I argue that as the conflict over the definition and treatment of children increased, it became one of the underlying causes of tension between African communities, especially the Kikuyu (the largest ethnic group in Kenya), and the colonial state. By situating children in the narrative of colonial Kenya, my research contributes to the growing historiography on children in Africa, as well as how childhood in the Global South was influenced by practices and legal conventions largely dictated by Western countries. A grounded historical awareness of the contested nature of childhood is important as global structures and organizations dominated by the West continue to influence conceptions of childhood in Kenya, and throughout the Global South, today.

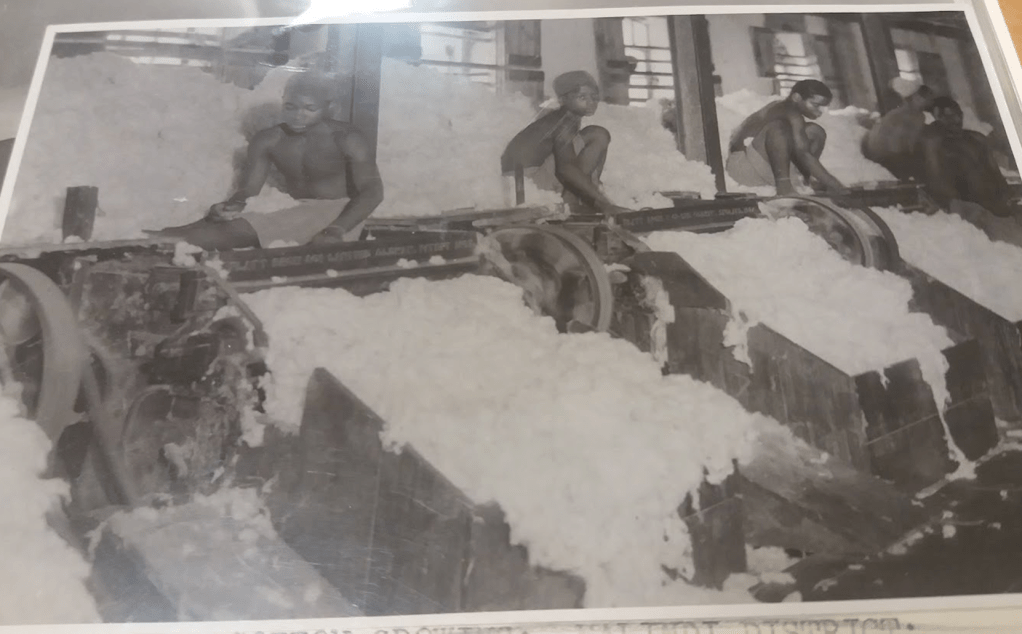

To illustrate how Kenya served as a “living laboratory,” my dissertation begins by examining precolonial conceptions of childhood among African communities in what became Kenya against a background of the transformation of the rights of children in Britain during the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. It then looks at the early conflicts over the treatment of children and the politics of generational and age-based power structures. By the 1920s, the growth in the power of the colonial state and missionary organizations led to an intensification of tensions over the control and treatment of children. This was evident in the instigation of the female circumcision controversy in 1928, where different beliefs regarding what qualified as “appropriate” treatment of children helped to cause broader social conflict. The controversy also exacerbated a growing desire by the Kikuyu to have control of their own schools and resulted in the independent schools movement developing in the 1930s. These schools, and the curriculum taught in them, became a critical space for the battle over competing conceptions of childhood, and the futures of colonial children. Concurrently, debates regarding child labor intensified. Colonial officials struggled to balance the requirements of International Labour Organization conventions with the desire to employ children in agricultural and industrial work in the colonial economy.

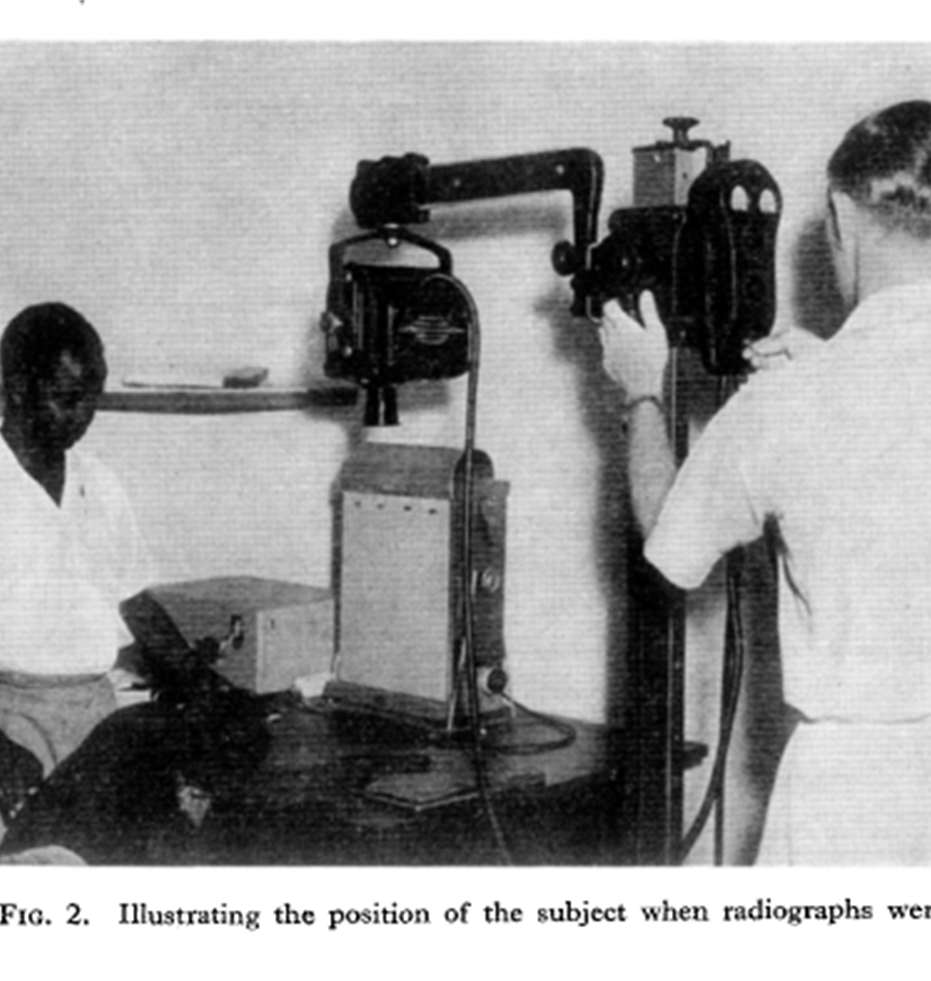

Finally, my dissertation examines how child-welfare became a space for the increased involvement of international organizations during the 1950s and 1960s. Groups like the Red Cross, Save the Children’s Fund, and UNICEF intensified their efforts to export Western conceptions of child welfare and the legal status of children into Kenya. Children’s bodies became further internationalized through efforts to establish a medical means of establishing age and efforts to combat childhood malnutrition. I argue that together these events show the centrality and pervasiveness of debates over the nature of childhood throughout the colonial period.